Rights Work: UChicago constitutional law course brings together incarcerated youths, law students

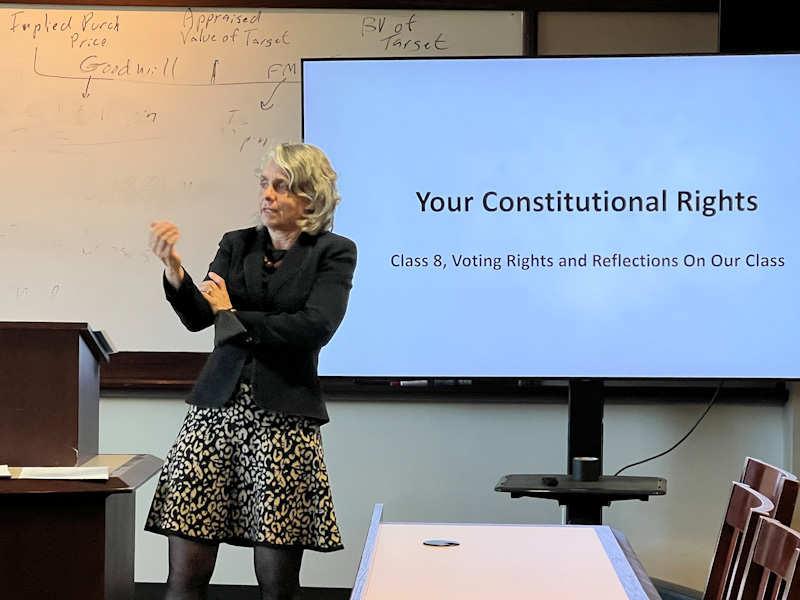

Emily Buss is a lawyer and a law professor at the University of Chicago Law School. She's also an expert on children and parents' rights and a member of the ABA’s Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar. Photo by Julianne Hill.

It’s the last night of a constitutional law course at the University of Chicago Law School. Tonight’s debate pits two groups of students against the other as if each is preparing a campaign for governor.

“What’s the most important constitutional right, and what would you change about it?” asks professor Emily Buss.

“The right to bear arms,” says a young man wearing a gray hoodie sweatshirt and a black skullcap. “You know, who can and can’t carry a gun, like felons.”

The opposing team agrees. “The right to protect yourself should be a right for everyone in the U.S.,” responds a young man in a long-sleeved gray T-shirt and jeans with closely cropped hair.

For a moment, the debate seems to stall until the only young woman among them speaks. “I don’t support the right to bear arms. I don’t think anyone should be able to have a gun.”

The participants in this classic debate on gun control aren’t the nine law students enrolled in the seminar. They are youths currently in the custody of Illinois’ juvenile justice system, participating in a UChicago Law-sponsored course titled “The Constitutional Rights of Young People, from Young People’s Point of View.”

The eight-week class is designed to give incarcerated youths an opportunity to consider their rights while exposing the law students to the younger students’ worldview through in-class discussions on topics that include freedom of speech, due process and reproductive freedom, along with weekly mentoring sessions.

“It is an extremely valuable experience for law students,” says Buss, an expert on children and parents’ rights and a member of the ABA’s Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar. “While engaging with young people who they’re very inclined to be supportive of, (the law students) are much more willing to pause and reflect about their own attitudes than they would be if they were just talking to people at the law school who had different views.”

Heidi Mueller is the director of the Illinois Department of Juvenile Justice.

Heidi Mueller is the director of the Illinois Department of Juvenile Justice.

Origin story

The seminar started five years ago with law students working in person with students from two UChicago-affiliated high schools. But when COVID-19 hit, Buss realized there was an opportunity to teach anyone anywhere. Working with her former student Heidi Mueller, now the director of the Illinois Department of Juvenile Justice, they brought the course online to kids involved in the criminal justice system.

Once the audience changed, the curriculum shifted too. Instead of its original emphasis on rights in schools, it became more focused on criminal and procedural rights, Buss says. A unit on the 8th Amendment was added, and the focus of the due process lessons shifted from school discipline to juvenile and criminal justice proceedings. Expectations for the law students also changed.

“We always do a training with the law students ahead of time to help them understand some of these topics can be really triggering for our kids,” Mueller says. “They have real life experiences of instances where their constitutional rights were not protected, or fighting for them and not seeing that they are being treated the same as others.”

Everyone agreed the online class, which ran in spring 2021, was a success, Buss says. “But we all said afterward, ‘Oh, if only we could have done it in person.’”

This spring, as the pandemic eased, administrators at UChicago Law and the state’s department of juvenile justice hammered out the logistics to allow students from three facilities near Chicago to meet in person. Half the classes are held in the Chicago juvenile justice facility; and half at UChicago’s law school in a classroom with a photo of former professor and U.S. President Barack Obama placed outside of it.

“Most of the kids who participate from the DJJ are young Black kids, and they get to take a class in the ‘Barack Obama room,’” Mueller says. “Many of them have mentioned feeling moved and motivated by that.”

Some of the students have graduated high school while incarcerated. Many are over 18. Currently, no college credit is offered for the class.

“I really feel like going on a campus was a big, big step for me,” says one participant who is about to be released after four months in detention. (The ABA Journal does not name those incarcerated in juvenile facilities.) “It made me change the way that I looked at college. I feel like the step for me is to lead right [to] it.”

‘More school than school ever was’

Each law student is paired with an incarcerated youth. Typically, they sit with their mentee during class, along with conducting weekly virtual one-on-one tutorial sessions.

Shayla Harris, an 2L interested in systemic justice issues, works to respect the younger students’ boundaries. “They have had a lot of exposure to violence,” she says. “As the course went on, and as they got more comfortable, they were more willing to share personal experiences.”

In the classroom, Buss starts with a short lecture on the topic of the day. Typically, the students then break up into small discussion groups, with each student’s law student/mentor sitting with them and facilitating. Next, the whole class participates in exercises, such as serving as someone’s lawyer or designing due process that meets their ideas of fairness.

“My favorite part of the whole class was how everyone debated, how you had to take control to get your point across,” says a young man who is hoping for clemency after serving three and a half years.

“It’s more school than school ever was for them. They have to articulate their ideas, make an argument when others disagree with them,” Buss says. “It gave them an opportunity to use their brains, to engage in intellectual exercise in a new way.”

Outside of class, the youths are assigned readings, like summaries of Roe v Wade. In their weekly one-on-one sessions, the law student and youths often watch videos on YouTube covering the next week’s topic.

Their relationship differs from one of an attorney and a client.

“It really was a two-way exchange,” Harris says. “Hearing how their interactions with the system didn’t necessarily align with some of the constitutional principles that we learned in the classroom, it really showed how things translate from in the classroom to in the courtroom.”

In her weeklies with her student, Harris moves the theoretical discussions from the classroom to practical applications. “I’d practice with him like, OK, so if you were stopped by a police officer, what would you say?”

Actionable toolkit

Each week, the law students write reflections considering how their thinking about the law, the legal process and constitutional rights has been influenced by their discussions, Buss adds.

“It was a really rewarding experience to know I was giving someone an actionable toolkit,” Harris says.

The class is an opportunity for the youths to see themselves differently. “These developmental experiences are so critical to positive and healthy identity formation,” Mueller says. “That is what leads kids to have hope, to be more successful, and ultimately to move on to a better path and not re-offend.”

As for Harris, the class offers lessons that will impact her career. “My main hope is that we all take this information and carry these perspectives with us when we go into practice,” she says. “If we do work on any one of these rights, we are thinking and taking seriously what we learned and heard from the youth.”

This story is part of the ABA Journal’s Children & the Law series exploring children’s law and juvenile justice.