New book details Justice Antonin Scalia's early life

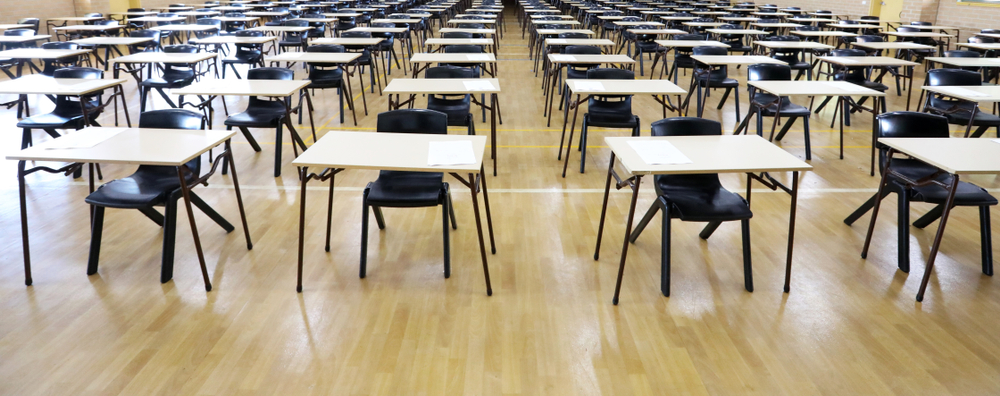

Antonin Scalia is sworn in as a U.S. Supreme Court justice by Chief Justice Warren Burger at the White House. Photo by Getty Images Bettmann / Contributor.

When the Senate confirmed Antonin Scalia to the U.S. Supreme Court on Sept. 17, 1986—Constitution Day—the vote was 98-0, a symbol of a less contentious era for judicial nominations.

The vote was a success for President Ronald Reagan’s administration, all the more notable because Congress had confirmed Justice William Rehnquist to succeed retiring Chief Justice Warren Burger that same day—although that 65-33 vote had been more controversial.

Scalia, then a 50-year-old judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, was attending a rubber-chicken banquet at a Washington hotel when John Bolton, then an assistant U.S. attorney general for legislative affairs, giddily called to inform him of the unanimous vote—minus two.

“Oh, that’s great,” Scalia said. But after a pause, he asked, “Who were the two who didn’t vote?”

The absentees were Sens. Jake Garn of Utah, who was in the hospital, and Barry Goldwater of Arizona, both Republicans. “Barry we just couldn’t find,” Bolton told Scalia over the phone, adding, “Nino, concentrate: We, we just won 98 to nothing.”

“Yeah, you’re right,” Scalia said. “That’s great. It’s great.”

This anecdote leads author James Rosen’s new nearly 500-page biography of Scalia, with Bolton telling Rosen in an interview that Scalia “wanted 100 to nothing.”

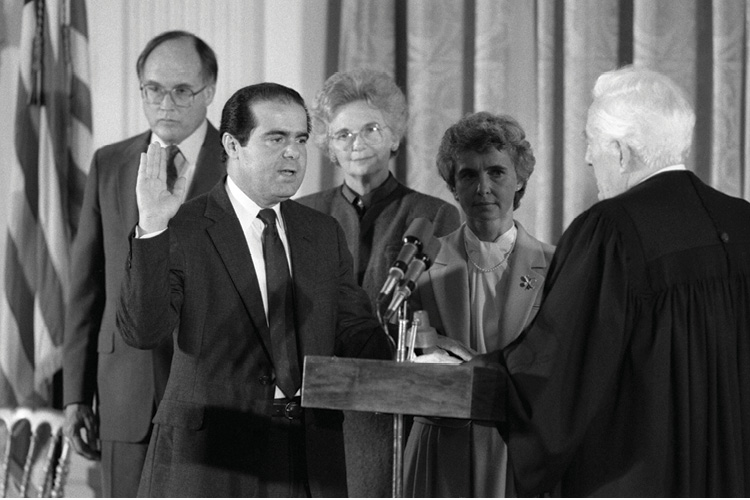

“This uncompromising commitment to perfection was a hallmark of the judge’s since his earliest days,” Rosen writes in Scalia: Rise to Greatness | 1936-1986 (Regnery Publishing). The book is the first of two volumes and covers Scalia’s early years and education, his jobs in private law practice, the executive branch, academia and the appeals court before closing with his swearing in as a justice.

Origin story

Photo courtesy of Regnery Publishing

Photo courtesy of Regnery Publishing

Scalia, who died in office in 2016, remains a revered figure among conservatives for his pugnaciousness, quick wit and his commitment to deciding cases based on “textualist” readings of statutes and an “originalist” interpretation of the Constitution. But Scalia’s combativeness also was polarizing, and his strong opposition to abortion rights, gay rights and affirmative action—along with his staunch defense of gun rights and the death penalty—have left a divisive legacy.

Scalia has been the topic of two previous biographies, more notably veteran Supreme Court correspondent Joan Biskupic’s 2009 book American Original, which included extensive interviews with him. There also have been book-length analyses of his opinions and a recent collection of the justice’s speeches, co-edited by his son Christopher Scalia.

So why is there another Scalia biography now?

Rosen, a former Fox News journalist who is the current chief White House correspondent for Newsmax, said in an interview that he had long admired Scalia and first pursued him as a subject upon arriving in the nation’s capital in 1999. Though he didn’t get the interview he sought, the two struck up a correspondence and had some lunches and car rides together. (Scalia was notorious for leading his passengers on white-knuckle rides. “Everyone who knew the man, it seems, had a horror story about his driving,” Rosen writes.)

“He was very generous to a young reporter all those years ago,” Rosen says. “So I resolved to write a book about him.”

This first volume traces Scalia’s youth in Trenton, New Jersey, and the New York City borough of Queens as the only child of Salvatore, a romance languages professor, and Catherine, a schoolteacher. Rosen describes his educational journey from P.S. 13 to St. Francis Xavier High School, a Catholic military school in Manhattan, to Georgetown University and then Harvard Law School. In one of Scalia’s first major disappointments in life, he was rejected for admission to Princeton University.

Rosen quotes Scalia once telling an interviewer that he detected a degree of ethnic and class prejudice by the Princeton alum who conducted that admissions interview: “I sort of had the feeling [that] he thought I was just not the Princeton kind of a person.”

While at Harvard Law, Scalia went on a blind date with a Radcliffe College student named Maureen McCarthy, taking her to a law review dinner. They would later marry, and she would become his rock. The couple had five sons and four daughters.

Early ambitions of ‘Il Matador’

This first volume by Rosen offers greater detail on Scalia’s pre-Supreme Court career, including his recruitment to be an associate at the Jones, Day, Cockley & Reavis law firm in Cleveland before turning to academia at the University of Virginia School of Law.

During the administrations of Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford, he held obscure positions where he honed his expertise in administrative law. As the general counsel at the Office of Telecommunications Policy under Nixon, Scalia “foresaw the internet,” Rosen writes, with a paper that predicted, in Scalia’s words, “long-distance shopping by TV” and “instantaneous home delivery of news.”

Rosen dubs Scalia “Il Matador” for his ability to sidestep and then lance bumbling congressional inquisitors with his wit and deep knowledge at his federal positions, which also included head of the Office of Legal Counsel in the U.S. Department of Justice.

When Jimmy Carter defeated Ford, Scalia went back to academia at the University of Chicago Law School, where he would often pile the family into the car to drive to a Catholic church where Italian priests were delivering the Mass in Latin. Despite sharing the conservative outlook of several of his prominent teaching colleagues, for various reasons Scalia was more than happy in 1980 to accept a visiting professorship at Stanford Law School.

The election of Reagan in 1980 initially brought disappointment when Scalia was passed over to become the U.S. solicitor general, but he later was appointed to the D.C. Circuit, where he worked alongside towering judges including Robert Bork, Laurence Silberman and fellow New Yorker Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Rosen throughout the book seeks to rebut what he contends is a long-running charge from some journalists and earlier biographers that Scalia’s rise to the Supreme Court was a “triumph of cynical, careerist cunning.” Yet Rosen also reveals a conversation Scalia purportedly had in 1959 with a Xavier High School classmate in which he said, “I’m going to the Supreme Court.”

“That does not rise to careerism,” Rosen argues of the youthful boast. “But it does resolve one of the enduring mysteries of Scalia’s life, which is when the ambition to serve on the Supreme Court began to burn in him.”

Rosen says he has started work on the second volume of the biography, which will cover Scalia’s years on the Supreme Court, and he has already interviewed Justice Clarence Thomas about his longtime friend and colleague. Rosen estimates that book to be at least two years away.

Toward the end of the first volume, Rosen details the scene in 1986 when Reagan brought Rehnquist and Scalia to the White House press room to announce their nominations. TV correspondents such as Sam Donaldson, Andrea Mitchell and Lesley Stahl tried to get the new nominee to open up about his judicial philosophy. But they were no match for Il Matador.

After some mangling of Scalia’s name (such as “SCALL-ya”), the correspondents finally asked him how to pronounce it. He told them. And then “SCA-LEE-a” made sure, over the next 30 years, that they would never forget.

This story was originally published in the June-July 2023 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: “‘I’m Going to the Supreme Court’: New book details Justice Antonin Scalia’s early life.”