May 8, 1867: Trolley segregation ends in New Orleans

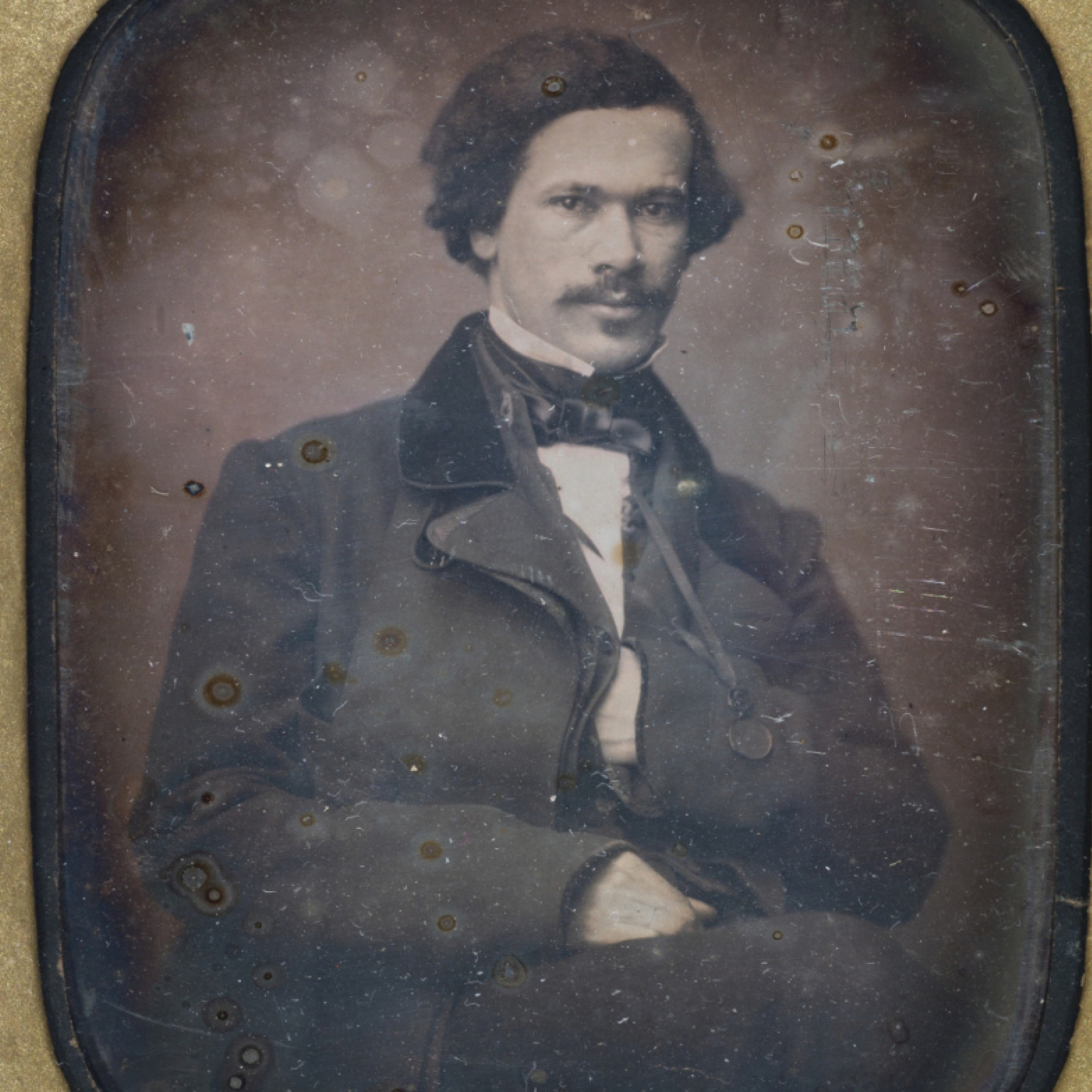

Louis Charles Roudanez. Photo from Wikimedia Commons

Since their inaugural service in the 1830s, streetcars were a source of both convenience and resentment for the Black citizens of New Orleans. With their access limited by local “Black codes” only to “star cars”—segregated trolleys emblazoned with a black star—even free Black workers, housewives and shoppers found a daily reminder that their freedom bore scant resemblance to that of whites.

Although the star car system saw protests over the decades, it was the New Orleans Tribune, a Black-owned newspaper founded in 1864 by Louis Charles Roudanez, a journalist and physician, that brought streetcar segregation to the fore. Emboldened by the presence of Union troops and Reconstruction sympathizers, Roudanez made the issue a stand-in for broader issues of civil rights.

New Orleans was always unique among American cities, both in culture and geography. At the advent of the Civil War, its metropolitan population of 180,000 included more foreign-born and residents of color than several Southern states combined. And its strategic location at the mouth of the Mississippi made it critical to the colonial ambitions of France, Spain and Great Britain as well as those aspiring to reunite the nation, North and South.

Having been seized and placed under martial law by the Union Army in April 1862, the city was spared much of the devastation suffered by other Southern cities. Its Black and mixed-race Creole residents, more educated and prosperous than their counterparts in other Southern states, saw hope that military occupation would resolve the brutal inequities created under colonial rule.

As early as 1724, Louisiana’s people of color—as well as non-Catholics—had been governed by codes noir, or Black codes, created under French rule. The first codes forbade non-Catholics from owning slaves and required slaves to be baptized Catholic. They prohibited slaves from carrying weapons, assembling publicly or selling goods on their own. Escape required a punishment of death or disfigurement.

But the codes also forbade owners from torturing their slaves or selling them apart from their immediate family. Moreover, slave owners could free their slaves for a variety of reasons. And once freed, former slaves enjoyed the rights, privileges and immunities of any free-born person.

Although the codes morphed with changes in governance, they created in New Orleans a cautious ease among races that evolved into a broad, if reluctant, acceptance of Blacks and mixed-race Creoles as part of New Orleans’ social life. Those freed could operate businesses, invest, attend churches and theaters and own property.

In 1864, while under Union occupation, the state’s legislature adopted a new state constitution that ended slavery but denied freed slaves the right to vote. When Reconstruction Republicans responded by reconvening the constitutional convention, the result was a deadly riot. On July 30, 1866, while meeting at the Mechanics’ Institute in New Orleans, delegates and their supporters were confronted by an armed mob that included local police and firemen. In the carnage that followed, at least 38 people were murdered and another 146 wounded, most of them Black.

Protests begin

In April 1867, with the massacre still fresh in memory, the New Orleans Tribune urged readers to confront the trolley issue and force “prejudiced associates to show their hands.” One week later, William Nichols, a Black man, did just that: He forced his way onto a white streetcar. After being tossed off the car by its white operator, Nichols filed a charge of assault.

For the next week, Black riders began boarding segregated trolleys. Their operators, under orders to avoid further confrontation, simply refused to move the cars. When a driver refused to stop for a Black cigar-maker, Joseph Guillaume, he jumped the trolley and drove it himself, only to be chased by police and arrested.

When Black and white mobs began to congregate at trolley terminals, the city’s mayor intervened, and by May 8, 1867, the trolley companies decided to relent. They ordered drivers to accommodate anyone desiring a ride. Their desegregation remained in effect until 1902, when Louisiana’s Jim Crow laws forced a resegregation that remained in effect for the next 56 years.